Re-reading recently the Italian art historian Federico Zeri's Dietro l'immagine: Conversazioni sull'arte di leggere l'arte, I was struck by a comment he made concerning Graeco-Roman figurative culture (that is, artistic culture) in North Africa and the Middle East; on page 41 he says: "It should be remembered, however, that the Graeco-Roman figurative culture, ... was an alien and imported [one] ...in north Africa and in the Middle East."1 This seemed odd as my mind immediately returned to the millennia-long figurative culture of Egypt, not to mention that of Babylon and others, all of which were thriving well before even the existence of Greek culture as such, let alone that of the Romans. Given that this fact would have been plainly obvious to Zeri of course, I began to wonder what he might have meant when he spoke of Graeco-Roman figurative culture: how did he see that culture as something alien to the north of Africa, given its very long (prior) history, especially in Egypt, of figurative art?

When I began to summon-up Egyptian art (which I must admit, I know only from books and western museums), what came to mind was tomb paintings and the black and red stone statues, large and small, of kings and queens, gods and animals. It then occurred to me that these examples were more or less dependent on line; even the statues, as realistic as they may seem, often retain an odd linear quality. And in so far as these works of art are based on line, they are also based on design. The clearer proof of this is of course the tomb (and other) paintings which are designed using line; these designs are then often 'filled-in' with colour, in the manner of in-laid metal work. Hence, the obvious 'indicative' - as opposed to 'imitative' - quality of the painted images is dependent on their straightforward but highly-refined linear design and not on mass or volume. In Egypt, the principal idea it appears was not to imitate what people saw, but to use what they saw to communicate (indicate) a concept: the concept of kingship, or power for instance, whether physical (temporal) or spiritual (eternal). Naturally, Egyptian statuary on the other hand, does have mass, more or less by definition, being solid three-dimensional objects. However, the stylised and simplified forms of the human body represented in massive statues have an awesome effect which is quite different from the more 'down-to-earth' quality of most Greek sculpture. 2

Egyptian standing figure, carved stone (no other details)

Boston Museum of Fine Arts (Photo: the author)

Note the rigidity and formality of the pose and how the arms are still attached to the torso; in spite of the broad stylisation of the body, the loin covering is worked with extreme delicacy and detail.

But let's return to Zeri's comment and have a look at what he was possibly getting at. It can be said that certain periods of 'western' art (as well as aspects of Egyptian art) aimed at a decidedly more 'imitative' result than others did: that is, the guiding principle of art manufacture (to some extent, independently of its purpose) was that of the imitation of Nature; indeed, in some instances, during those same periods, there was the further aim of actually bettering Nature by selecting the best parts and combining them into something closer to an intellectual ideal (Alberti, Leonardo). Certainly, those aims are manifest in not only the development (the evolution) of Greek art - and carried on by the Romans - but particularly in its classical and Hellenistic (from 323BC) periods. This imitative desire clearly implied mass, as the objects which the Greeks wished to represent, the human body especially, require an understanding of and an ability to convey mass. Both Egyptian and Graeco-Roman cultures represented the natural world in three dimensions, that is in statuary, using stone, granite for instance in the case of the Egyptians, marble in the case of the Greeks and Romans, and both also made sculpture in bronze, life-size or larger or smaller. Sculptors understood mass not only as a by-product of working in stone (or wood), but also how to create it in what is essentially a shell, that is, a poured bronze sculpture. 3

The Boxer (Il Pugile), Greek, fourth (?) century BC

Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, Rome (Photo: the author)

This extraordinary bronze statue, slightly larger than life-size, was made using the 'lost wax' method; it was found buried under metres of soil and rubble during excavations in Rome. Note the figure's occupation of, or extension into, our space and, incidentally, the subject itself: a subject apparently worthy of the considerable effort and time, not to mention money, required to make such a statue.

The impression of mass was not restricted to sculpture in western art but was an aim also in painting, especially in the Renaissance. Together with line, the use of colour as an independent 'stuff' to imply or represent mass is completely different from its use by the Egyptians. Various periods of western art have been more or less dependent on line, not only as a basic design element, but also as a formal element in its own right. Looking at the Italian Renaissance, we can see that in cities like Florence, Ferrara and others, line played a critical role, not only in the drawing phase of the preliminary sketches and the picture design, but also in the finished painted image. And although initially also Venetian painting was visibly dependent on line, ultimately colour as mass began to dominate (in late Titian for example). A curious exception to this in Florence incidentally, is one of the frescos by Masaccio, an early Renaissance master, namely the Brancacci Chapel Tribute Money (1425): although still linear in many respects, already, in some areas, Masaccio is rendering his forms and their mass mainly with colour (in some of the clothing but especially in the background landscape).

In Florence, drawing - referred to as disegno by Vasari - was of paramount importance; in numerous pictures of the Renaissance, both in frescos and on panels and later, on canvas, the importance (and astounding mastery) of line is everywhere to be seen. The Florentine dependence on line in some cases is so strong that the final painting can look like a coloured-in drawing. This dependence can be understood by studying the 'sinopia', the underdrawings of detached frescos, many of them now displayed as quasi-independent works of art 4; aside from the manifest mastery of drawing in and of itself, the integral relationship between the sinopia drawing and the completed coloured painting is plain to see: the finished painted forms maintain their 'mould' of line, in spite of the form-modulating colour. And artists further north in Italy as well, in Ferrara, Mantua, Venice and so on, artists such as Carlo Crivelli, Cosmè Tura, Bartolomeo Vivarini, Andrea Mantegna 5, Francesco del Cossa, Vittore Carpaccio and Giovanni Bellini, are clearly dependent on line: line defines and encloses their shapes and their forms, it is a kind of phantom surface pattern coexistent with the depth and volume they want as the primary first impact; sometimes, the surface-sitting line contradicts the work of the colour, sometimes insists so to speak, too strongly on its own life! 6

Giovanni Bellini, Madonna adoring the sleeping Child, mid-1460s,

tempera on wood. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. (Photo: the author)

In this exquisite picture by Bellini, the linear aspect is obvious and fundamental; the typical result of this dependence is a clarity and forthrightness of statement.

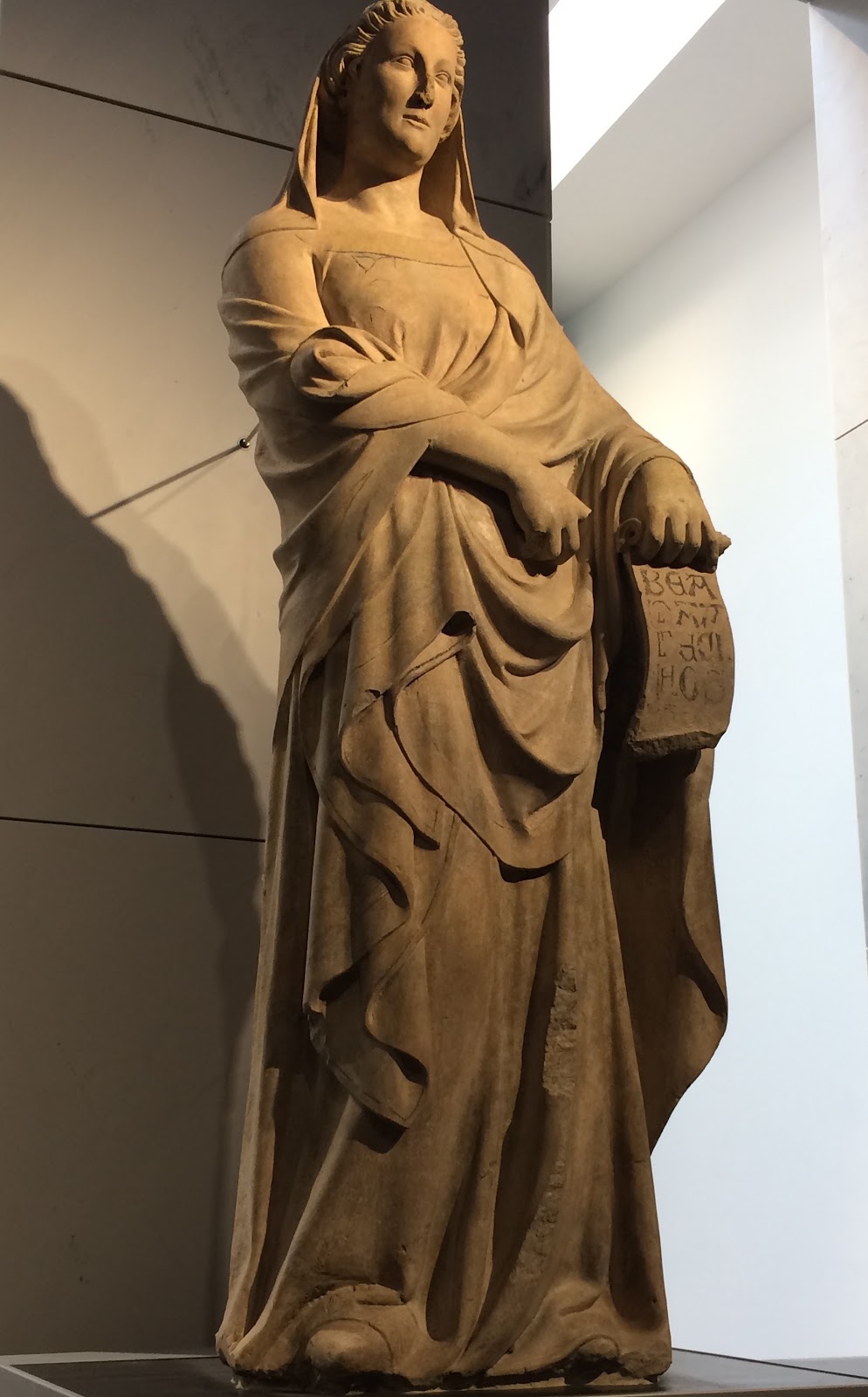

Although as just stated, some Florentine pictures look rather like coloured-in drawing, and the same observation was made earlier concerning Egyptian painting, what then is the difference, if essentially, both cultures were doing the same thing? The answer is to be found in the intent: as suggested, Egyptian artists were interested in the imitation of Nature (in their formal hieratical art) only to a certain extent: Nature served as an accessible visual sign of an abstract concept but was not itself the goal (notwithstanding this, there is a small body of extremely life-like portraits, such as that of Prince Ankhhaf [2520-2494 BC], a painted limestone bust in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston). In Renaissance Florence on the other hand, line was used to 'describe' the abstract contour of a given form (a facial structure, a limb, a twisting torso) but in such a way that it 'implied' the muscular function which produced the particular form or action; this latter characteristic taken to an exceptional degree by Michelangelo. Egyptian art is on the whole static, it was not intended to portray movement for its own sake, and where there is movement, it is described by characteristic position and shape - not by detailed and subtle description of the mechanical functioning of human anatomy. Renaissance art - painting and sculpture - by contrast, was deliberately aiming at the convincing portrayal of movement (amongst much else) 7. Line was the incipient fundamental, the line produced the contours - as in Egyptian painting - but 'formed' the muscles, that is, it realistically protracted the movement from one part of the body to another, or into the surrounding space; it took its lead in this movement into the ambient space - which of course is the space of the viewer - from the Greeks and the Romans. Interestingly, as far as sculpture goes, in Florence and elsewhere in Italy, as with Greek sculpture itself, there was a slow emergence from the basic squared block of rude stone out into the open space surrounding that block; in Nino Pisano and even in early Donatello, we see examples of the 'confinement' of the block; Giambologna, in the next century, is an example of attained freedom from the squared stone.

Nino Pisano, Sibyl of the Tiber, 1337-41, marble

Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence (Photo: the author)

Donatello, Thoughtful Prophet, 1418-20, marble

Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, Florence (Photo: the author)

Giambologna, The Rape of the Sabine Women, 1579-83, marble

Loggia dei Lanzi, Florence (Photo: the author)

By implication, we now come into contact with another concept, that of 'space'. Fictive space, illusionistic space, is almost - but not quite - wholly absent from Egyptian painting; generally speaking, we can say that Egyptian painting is 'flat' and has little or no interest in rendering depth, although it is sometimes implied. Greek sculpture (and what we know of its painting) moved slowly but surely away from this norm, eventually creating actual space within individual works and then 'bursting' out of that confine altogether and into our 'real' space; by the time of the Hellenistic period, the norm was movement in space, in 'real' space. I stress this because, although (especially large) Egyptian sculpture obviously exists in real space, that is, it occupies real space, it nevertheless maintains at least a psychological restraint, perhaps a spiritual distance, from the viewer: it is in our real space but, at the same time, somehow separate from us, we who occupy, apparently, the same space!

A further development of the suggestion of mass as it occurred in Renaissance Venice is evidenced in the work of Titian (c.1490-1576). As he got older, his work moved further and further away from what might be termed a 'linear illusionistic realism' and towards a dissolution of both the pictorial surface and the modelled form, both with the same means: that is, by allowing the mark of the dragged brush to assume an active role in both the construction of form and the indication of light and texture. Such development could hardly be more antithetical to Egyptian aesthetics while hardly being less so to Florentine 'disegno'. Pictures such as the London National Gallery's Death of Actaeon (1565-76), the St. Louis Art Museum's Ecce Homo (c.1570), the Hermitage's Saint Sebastian (c.1575) and to some extent the Prado Self Portrait (1560), while obviously begun with line, all abandon or supersede it with colour and (paint) texture. The drag of the brush becomes a bravado serpentine line of paint, it indicates but does not describe, it is surface for its own sake, an active pulsating surface moving independently of any drawn contour. 8

It would appear that Federico Zeri's comment on the alienness of Graeco-Roman figurative culture relates to a bi-lateral circumstance: a difference in intent, a difference in the function of 'reality' or Nature; and a difference in formal means. The roundness and dynamism of classical Greek sculpture, its mimetic insistence, its life outside the squared block of stone, its consequent 'intrusion' into our real space and its rejection of frontality are indeed all alien to the hieratic Egyptian view. 9 So too in painting, if pictures such as the first century BC Alexander and Darius mosaic from Pompeii may be taken as examples: a 'chaos' of contrapposto movement across the field, the interplay of glances, the array of emotions and actions (expressed marvellously also by the horses), the dramatic human reality of the scene: all un-Egyptian.

1 Federico Zeri, Dietro l'immagine: Conversazioni sull'arte di leggere l'arte (Behind the image: Conversations on the art of reading art), published by TEA Arte, 1990. The quote from p41: "Bisogna ricordare, però, che la civiltà figurativa greco-romana, .... era una civiltà aliena e importata ....nell'Africa settentrionale e nel Medio Oriente." It might also be argued that, far from being 'alien' to north Africa, Greek sculpture can be seen as a development out of pre-existing Egyptian models; when we consider the first 'kouroi' of Greece, with their rigid frontal poses and their tentative one step out of the stone block, we are immediately reminded of that same pose in the earlier Egyptian sculpture.

2 We need to keep in mind, when we discuss in the 21st century the distant past, our very different and possibly erroneous perception of the significance of ancient statuary and the fact that we usually see it in museums, absolutely out of its original context, not to mention that much of it was polychrome! For instance, we are by now habituated to appreciating ancient Greek sculpture as monochrome whereas, in fact, much of it (including its architecture) was colourfully painted. As for the Egyptians, who tended to stylise their representations of human beings (and gods), curiously their painted and carved narratives are nevertheless full of very accurate renderings, clearly observed from life, of ordinary farmyard animals, such as ducks! This indicates that they were in fact more than capable of drawing what nature put in front of them and that, as a corollary, their stylised imagery was a choice, not therefore an inability to render accurately.

3 Bronze casting and the 'lost wax' method were known to the ancient Egyptians, however their use of bronze statues seems (as far as I know) to have been mainly for smaller household and votive objects. In any case, generally these items lack the robust fullness of their larger works in stone.

4 One example which readers of my articles will be familiar with is the oft-cited detached frescos with their 'sinopia' mounted on the walls of the small Florentine (now-)museum of Sant'Apollonia, the work of Andrea del Castagno.

5 Andrea Mantegna's Arrival of Cardinal Francesco Gonzaga in the Camera degli Sposi, Mantua (1474), is an example of the 'persistence' of line. Although beautifully coloured and suggesting depth, it remains curiously (and, presumably, unwittingly) similar to Egyptian methods: the foreground figures are represented frieze-like across the surface, in static - and statuesque - poses, quasi-hieratical, silent and largely expressionless. All the figures and the background landscape are utterly dependent on line; the image is in effect, a coloured drawing. (Not for this however, any the less beautiful!)

6 I imagine that many readers will be saying to themselves that "of course drawing is fundamental, how else do you plan and layout a picture - and other types of artwork - if not with drawing?" Naturally I agree with this observation but the use of drawing per se is not the point here: the point is the impact of drawing on the final appearance of a given artwork, especially of one in two-dimensions. With the development of en plein air painting in the 19th century, normally related to landscape pictures, drawing, although not for the first time, did not have a critical role in the finished image (Turner's late 'abstracts' are another example; some of Corot's Roman pictures on the other hand, are based on preliminary line work); sometimes, the merest indicative lines (of placement, that is, composition) were used; eventually this often alla prima technique spilled over into both portraiture and still-life, at least in some areas. Later, paint itself as line, a kind of reversal of the norm, may be seen in the pictures of a Giacometti for instance.

7 In A World History of Art (Guild Publishing, 1975), Gina Pischel says on pp107-8, when discussing influences on Hellenistic art: "Besides, other insidious aesthetic demands ... made themselves felt. These ranged from exterior exigencies .... to the more inward ones of the passionate search for realism and free movement."

8 To some extent, Titian's technique and that of similar painters, particularly those who came later - Valezquez (1599-1660) for instance - depend in part on the more common use of canvas (as opposed to wooden panels) as a support, together with a greater understanding of the possibilities of oil paint (as opposed to tempera). Very large canvases became popular in Venice especially, as well as a more pronounced weave, somewhat finer weaves being preferred elsewhere.

9 In relation to frontality however, a curious phenomenon is the so-called 'Fayum' portraits. These portraits of the time of the Roman occupation of Egypt were used like contemporary 'photos' of the deceased and as such, were placed on or in their mummies, in place of the traditional Egyptian stylised face and head. Often, these portraits, painted on wooden panels in encaustic, show the deceased in a three-quarter view; this of course, is completely against the standard fully-frontal representation of Egyptian funerary practice. It would appear that the Roman occupiers (and perhaps before them, the Greek settlers), while having adopted certain of the local customs (as was their wont), nevertheless preferred their own art form when it came to memorialising themselves. In this they managed to introduce, albeit in a minor way, Graeco-Roman movement - and particularity - into Egyptian stasis and stylisation! (see Three Painted Portraits in this blog for a fuller discussion).

Apologies to the reader for the heterogeneous appearance of the text; despite my best efforts, the site seems to have a mind of its own and reproduces what was established in the Draft in any way it chooses!