As for all art students, at least of the past, Giotto was for me a 'house-hold name', a 'given' of art history, even if I understood precious little of his 'revolution'. I had seen the beautiful basilica once before, many years ago, but had understood nothing; Giotto however became an integral part of this more recent journey. My interest in any case had been strongly stimulated by the classic exegesis on the part of Luciano Bellosi, his La Pecora di Giotto (Giotto's Sheep)1. For anyone who has not seen the stupendous cycle of frescos by Giotto in the Basilica of Saint Francis, I recommend it as wholeheartedly as I possibly can: a profound experience not to be missed by anyone interested in art and who chances to be in Italy.

The 'revolution' worked by Giotto is made plane by its being situated not only in its original ambience, but also in one of the most marvellous de facto 'art galleries' in the world. I say this because his Stories of the Life of Saint Francis are in the upper basilica along with the work of several other masters, including Cimabue, but there is also the lower basilica containing not only other Giottos but as well, the works of Cimabue, Simone Martini and Pietro Lorenzetti, not to mention other frescos by unidentified or at least, 'disputed' masters. In fact, the real identity of the authors of many of the paintings in this extraordinary 'gallery', including those generally ascribed to Giotto, is disputed by art historians; then there is the question of just how much of the agreed Giottos is actually by his hand, that is 'autograph', and how much was done by assistants.

That said, the present article is concerned, mainly, not with the analysis of the scenes as narrative, but rather with the way in which Giotto has handled space and particularly, with his 'built environment' or, more prosaically, his buildings! Luciano Bellosi was extremely interested in this aspect as well and I freely admit a debt to his writings in this instance. However, I think there might be one or two things of interest not especially noted by Bellosi although my own 'awareness' of their existence was certainly cultivated by being familiar with his thesis.

As discussed in other articles in this series, the (apparently accurate) representation of space is one of the fundamental 'conquests' of the Renaissance, a conquest that was either not required in preceding periods of art history or was positively rejected in later ones, such as Mannerism, and notably again in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. At the time of Giotto, and in the case of Giotto, we could say there was clearly an intuitive awareness that 'space' as conceived of in Byzantine painting - the dominant style in Italian religious pictures - was no longer doing the job required by the developing 'independence' of certain Italian painters.2 This new requirement for a logical space, as opposed to a 'spiritual' or transcendental one, came hand-in-hand with other changes in Italian culture at that time (late-13th and 14th centuries), changes related to literary studies by nascent humanists (in France and Italy) and, in Italy, an awakening interest in classical art and architecture, especially the at-hand Roman variety.

To varying degrees, ancient Roman artists appear to have had a fairly good grasp of something similar to mathematical perspective, but because a rational, realistic space (that is, with the use of perspective) had not been required by the Christian church after the period of late-antiquity, the focus being almost entirely on the transcendent implications of religious imagery and not on its approximation to external reality, the knowledge of how to 'construct' such a rational space had eventually been lost. Giotto and others however began to feel the need to place their narratives into more convincing spaces, that is to say, to represent space, and especially buildings, more and more as they actually looked to the 'modern' western Christian - as indeed he was doing with his figures! Giotto's figures are what sets him apart in the first instance and this is clearly obvious in the accidental 'art history lesson' which is the Basilica of Saint Francis. If we start in the lower basilica by looking at some of the earliest frescos there, and at Cimabue, and then move on to the upper basilica, the new 'description' of human beings wrought by Giotto is, simply, astounding. To be clear, all is beautiful, in both the lower and the upper basilicas, but the abrupt transition from late Byzantine to 'modern' art is patently visible.

Given this, as said, I would like to discuss some aspects of Giotto's exploration of space as seen in his buildings in the frescos in the upper Basilica of Saint Francis. Some representations of buildings - usually invented but, sometimes at least, based-on actual ones - attempt to convey a sense of reality by 'splitting' the visual data into what can or would be seen if the hypothetical viewer were looking down, and what he or she would see if looking up; these two points of view are usually merged in the one building or structure, as well as, sometimes, what would be possible if the viewer were turning his or her head from left to right. One characteristic however of the painting of this period of 'proto-perspective' is its inconsistency: to put it simply, some things are coherent within the limits of the scheme while others are not, and this within the same structure (building, desk, baldacchino, etc.). In other words, the approach was mostly intuitive, there being, at that point, no 'mathematical' process to adhere to - as later became the norm with Renaissance perspective. But the attempt was definitely being made and especially by Giotto.

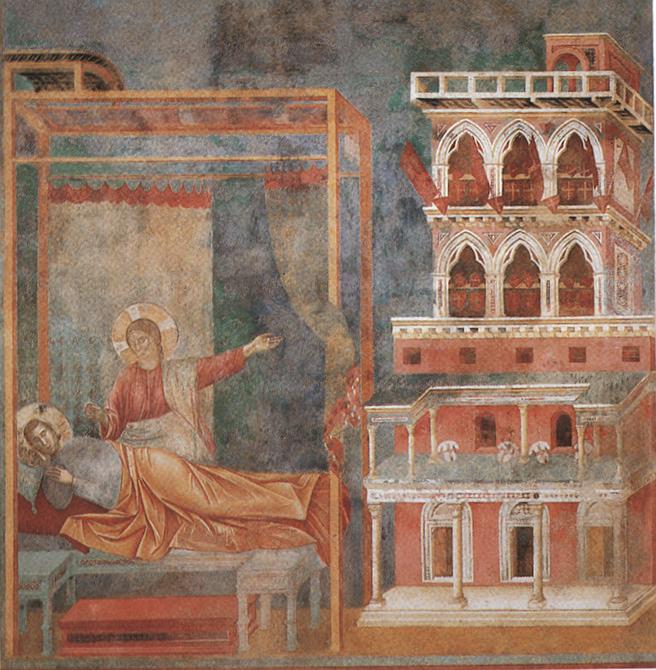

Let's start our analysis by looking at the scene called The Dream of Francis at Monteluco (below). In this image, divided into a left part and a right part, a large imagined building occupies the whole right side; there is a structure on the left as well, but it belongs to an earlier and more common conception of a single room. The palatial structure on the right occurs in a dream foretelling Francis' future; when studied closely, it becomes clear that this building is rendered in the manner described above: the lower part, with its pale green loggias or verandas, is represented as we would see it when looking down; in the middle, that is, the junction of the lower part and the upper part, there is little if any suggestion of space (in fact, it is a de facto horizon line); above that line, we are supposed to be looking up, as we would if looking at a tall, substantial building (note the undersides of the arched windows and of the terrace on the top). The problem is that the views are inconsistent: it is impossible for us to look down on the lower part of the building from our presumed standpoint (near the right edge of the painting), this because we would need to be quite a distance from the structure as well as quite high up; in fact, our eye-level, on the left side of the scene, seems to be more or less at that of the dreaming Saint Francis, but, on the right, where the palace is, our eye-level is coincident with the horizontal mid-line of that building, at its 'horizon line'. For us to see in real life a building with such a discrepancy between the 'down' view and the 'up' view, either we or the building would have to bend quite a bit backwards, the building thereby forming a convex structure! In short, if we are able to look directly at the reclining figure of Saint Francis, we could not possibly be looking down at a building so close by. It should be explained that, even in mathematical perspective, we can see 'up' views and 'down' views of the one structure but, because of the vanishing point system, those views are wholly consistent with one another.

Nevertheless, Giotto has perceived some aspects of 'real' vision correctly even if he hasn't known how to represent them coherently: on the right side of the palace, both the bottom and the top orthogonals do incline correctly (upwards and downwards respectively) but other orthogonals on that side do not; the reason is that there is no assumed or fixed 'vanishing point', a basic element in normal perspective drawing, so the orthogonals wander off willy-nilly, sometimes consistent with the 'perspective', sometimes not! Those of the 'room' on the left do in fact recede to completely different 'vanishing points', to the extent indeed where the use of the term 'vanishing point' is redundant. Of course, as the much later Surrealism and Dada have demonstrated, anything is possible in a dream and this image by Giotto actually seems to be, so to speak, 'caught' between an attempt at 'realism' and the liberty inherent in the representation of a dream!

Although not immediately pertinent to this discussion, it might be noted that the lower part of that structure is a 'classical' building (of a type that can be seen in ancient Roman frescos interestingly), with columns and capitals and rounded arches, whereas the upper part is Gothic (and in a different scale), that is 'modern' or contemporary with Giotto's own time; the pointed-arch windows with their elaborate mouldings and the contemporary shields (barely visible through the upper windows) would seem to have some symbolic function, perhaps indicating the 'modernisation' of the church by Saint Francis.

Now let's turn our attention to the fresco called Francis exorcises the Demons from Arezzo; again an image divided into two parts, although this time physically linked by the figure of a friar. On the left side, behind the praying figure of St Francis, is a very large structure, possibly representing a cathedral; this representation is extraordinary in its attempt to show a large Gothic structure, in fairly accurate detail (there is another in the scene of Saint Francis mourned by Saint Clare). The architecture closely resembles the form and style of a large contemporary church, and the viewpoint is by-and-large consistent (that is, from below looking up from the right). The polygonal apse doesn't quite work but, generally, a successful and original description. On the right side we find one of two famous depictions of the medieval city of Arezzo 3, not a 'portrait' of the real Arezzo but a kind of synthesis of medieval Italian hill-top cities. What is of interest here for our purposes however, is the drawing of this city: because Arezzo is on a hill, it is reasonable that the buildings within it, as it were, 'climb up' that hill and so the depiction is rational in that sense, and in its being shown from below. But what is especially rational is Giotto's observation of a particular visual fact: here we have an example of the movement of the viewer's eye as he or she stands in one particular position - and that position is clearly indicated by certain 'physical' facts.

Our position is indicated by the fourth merlon (the v-shaped raised part on the battlement) from the principal city gate, on the left; that merlon is shown full-face, that is, we can't see its sides. The merlons to the left and right of the fourth one are shown not only with their front face but also with either their right side or their left side; this is how we would actually see them were we positioned at the point suggested. In addition, we can see the right side of the main gate, and the left part of the inside of the gate, as we can equally-well see the right side of the inside of the minor smaller gate to the right. The merlons on the main gate itself are also drawn so as to be consistent with our point of view. What is clearly a 'contradiction' of these structural facts is the size of the figures coming out of those gates, a perhaps necessary hangover from medieval tradition. In fact, all the scenes have this characteristic, that although the artist has patently been observing the real world in which he operated, he was nevertheless constrained by certain established norms of narrative: for instance, in many but not all of the images in the cycle, the principal actors are arranged, frieze-like, parallel to the picture plane. In terms of spatial arrangement of figures, an exemplary later contrast might be for instance, the Death of Saint Matthew by Caravaggio, in San Luigi dei Francesi in Rome (see photos below).

Next, the scene known as The Homage of a Simple Man. This image is interesting because it differs from the two previously discussed in that the background buildings form a continuous screen or 'curtain' behind the action of the drama; there is a division into a left part and a right part but this is achieved by the groups of figures and not by the buildings, as in the other cases. In fact, the space between the two groups is 'filled' by a temple; this temple actually existed in Assisi at that time and still exists today: it is the Temple of Minerva, an ancient Roman structure in the centre of Assisi, which later, like many such buildings, was converted into a church (Santa Maria sopra Minerva). Giotto's use of this real structure did not however prevent him from adapting it to suit the formal requirements of the scene.

The real Temple of Minerva has six columns in its facade, not five as in the fresco, and none (today at least) within the peristyle (the area between the columns and the front wall): Giotto has two such columns on either side of that 'porch'. Giotto's front wall is just a simple wall with two iron-grilled windows and no door (the temple was at one point the city prison); the current front wall has no windows but a very large central door. What is common to both the present building and its painted image is the herring-bone patterned brick pavement in the area of the peristyle, so beautifully depicted, if simplified, in the fresco. Giotto has also added a 'rose' window to his enlarged timpanum, a completely anachronistic structural element; as well, he has decorated the architrave (the straight beam supported by the columns) with a mosaic style known as 'cosmatesque' (or, Cosmati work), again completely anachronistic for a Roman temple although very popular in medieval religious buildings. The artist's columns are notably much thinner than those of his model (in keeping with the thin and somewhat elongated aspect of the other structures, perhaps a reflection of Gothic influence), thus appreciably reducing the pagan robustness of the real structure. But why did he paint this building with only five columns instead of the actual six, and those so lean? I would suppose that, while wanting to include this reference - a genuine landmark - to the contemporary city of Assisi, he nevertheless had to make it 'work' as part of his composition; the image is not about the temple - it's a reference, not a portrait - but that reference serves to reinforce the 'actuality' of the scene which historically took place in Assisi.

The tower next to the temple also still exists although now with a low addition on its top. But for this article, the interesting thing is the construction of space and objects; we have already remarked the 'frieze-like' disposition of the figures, from left to right across the foreground, and the theatre-like 'curtain' background of the buildings. But, although the artist has positioned us as so we can see the right side of the buildings, including the temple, those figures are all seen from directly in front! This presents a contradiction because, although the figures can of course be arranged similarly in real life, their position relative to us (or to the temple) should be different: if we can see the right side of the buildings, then we could also see different sides of the figures as well; that is, some from the back or from a three-quarter back or front view, and so on. And again, the figures appear to be out of scale in relation to the buildings: they can seem very close to the background although the size discrepancy may mean to indicate distance between the figures and the buildings (the figures are closer to us). If that were the case, there would seem to be another contradiction because unlike in, for instance, contemporary manuscript illumination, there is no indication of so-called 'atmospheric' perspective, perhaps best illustrated by the backgrounds of certain pictures of Leonardo da Vinci 4. Clearly, the figures and background are not so distant from one another as to seriously reduce the tonal value of the colours of the buildings, but there is nonetheless no clear indication of what I might call 'planar' separation (the relative positions of objects in different planes starting at the 'front' of an image and moving progressively further into the fictive space: a wonderful example being Donatello's Banquet of Herod bronze relief panel in Siena).

In terms of a formal analysis of the 'perspective' in The Homage of a Simple Man, we have an example of what the art historian John White called the 'foreshortened frontal' view 5, that is to say, a full-frontal view of one side of a given structure with one other side attached, usually with some intuitive 'perspective' elements: in this case, the front of the temple with its (viewer's) right side suggesting diminishing (perspective) recession (as was the case with the first scene we looked at).

A curious 'omission' on the part of many painters at this time, including Giotto at Assisi (and in his panel picture in the Louvre of Saint Francis receiving the Stigmata), is the almost total absence of shadows cast by the human figures! Despite the fact that their clothing is forcefully represented with the use of light and shadow, and that the light-source is generally consistent, the figures themselves - and objects for that matter - throw no shadows on the ground!

Giotto nevertheless made great progress towards an internally coherent representation of a three-dimensional structure: let's look now at the scene known as Pope Honorius III listens to the preaching of Saint Francis. Here we see a room, closed on three sides and open, although divided by two columns, at the front; in fact there are four columns which together serve to 'segment' the scene into three distinct areas. The central area is occupied by the Pope, who is seated on a raised throne, as well as two members of his entourage; in the left segment is Saint Francis in the act of preaching; he is accompanied by a companion who, being seated on the floor with one leg behind the dividing column, thereby links that left space with the central one of the Pope. The right segment is occupied by another three attendants; all of these members of the Pope's entourage are seated on a curved yellow-ochre bench: this bench links all three segments of the image at this level, beginning as it does with the attendant in blue, making up the third person in the left segment. As can be seen, there are three 'actors' in each segment of this image, all more or less on the same level except for the Pope who is naturally higher than the others, and the oddly casual figure of Francis' companion, sitting on the floor! Francis is however, the only person standing.

'Linking' is achieved as well in other parts of the fresco: for instance, along a kind of middle line is hung - or painted - a curtain which runs along all three of the closed sides of the room. Above that, so to speak, in the upper foreground, is the Gothic architecture of the forward face of this structure, its pointed arches repeated in the ceiling structure of the room and in the five bi-forked windows of the rear and side walls. We know there are side walls because the angle of the 'curtain' decoration and of the extreme left and right windows recedes very gently towards some central point. More importantly, Giotto had 'centred' the ceiling arches so that we see the central part from the centre, and the two side parts are convincingly seen as they would appear in real life to a viewer standing where we are, that is, outside the centre of the structure. But, there are two inconsistent elements in this scheme: the first is the yellow-ochre floor. In the lower left corner, the artist has caused the pattern to recede 'correctly' to the centre but, in the middle of the floor, the area 'below' the Pope's throne, the pattern follows the old medieval practice of simply 'climbing up' the image: it is not shown as consistent with a floor which is receding into the fictive depth of the painting!

The other inconsistency is the throne itself. Naturally, such a construction can, in real life, be situated in any position that seems appropriate and here it is so situated to emphasise the attention of the Pope to Saint Francis's preaching. The problem is that there is no attempt to represent that throne consistent with the strong, pervasive 'perspective' in the rest of the composition! Like that part of the floor it sits on, it has a life of its own, independent of what has been attempted elsewhere in the same composition.

A couple of points in relation to this scene: again, no shadows cast be the actors, nor by the throne, despite the clear dependence on light and shade in the modelling of the heavy clothes worn by those same actors. And I must mention the extraordinary life-likeness of the expression on the Pope's face as well as the incidental detail of his holding his sash in his hand: quite amazing observations of ordinary 'human' traits, so different in fact from the hieratic tradition of what came before Giotto, and indeed was still the norm in his own life-time.

In concluding, I would like to draw attention to some objects included in both The Invention of the Crib at Greccio and another scene called The Verification of the Stigmata; in the former work, astounding in its innovation in any case, Giotto has painted a wooden cross, seen from the back, as it leans into the nave of the fictive church. Such wooden crosses are very often enormous structures, several metres high, painted on one side and, on the other, held together by robust carpentry, visible, as here, from the rear; in fact, several such icons were painted by Giotto himself. What is of particular note is that we see this object from the back, almost a blasphemous act! Indeed, one of the 'hallmarks' of Giotto's frescos is his 'penchant' for rear views, normally of people, but, as here, sometimes also of objects. In the Stigmata episode, again set within a church, we are seeing the event from the nave and we know this because this time, we can see the painted sides of three icons suspended above or on the rood-screen (a screen which once separated the nave from the choir or altar area in churches) 7.

In this scene, the three icons are, from the left, a Virgin and Child, a Crucifix and a Saint Michael Archangel; according to some, the Crucifix represents a real one - there were two - made by Giunta Pisano (commission 1236) for the Basilica itself 8. Giotto has here attempted another device to indicate the space in which this event occurs by showing these icons leaning into it in the way such pieces actually did. Today, the rood-screens are gone and frequently these large Crucifixes are hung either in the nave itself or on a wall but originally they decorated the screen on the 'lay' side, that is, the side within the body of the church.

1 La Pecora di Giotto by Luciano Bellosi, my edition published by Abscondita in 2015. The title of this fundamental text comes from the apparent 'legend' which recounts that Giotto, as a boy, was 'discovered' by Cimabue who became his master: that the young Giotto, while minding his father's sheep, would amuse himself by drawing them. Cimabue, happening to pass by one day while Giotto was thus occupied, immediately recognised the boy's talent and convinced his father to allow him to take Giotto as an apprentice.

2 I stress 'painters' here because at more or less the same time, the sculptors Nicola and Giovanni Pisano (father and son) were, so to speak, skipping the Renaissance - of which they were in fact precursors - to arrive at a kind of paleo-Mannerism: their conception of space in the pulpits and other works in Pisa, Pistoia, Prato and Siena, with their crowded massing and piling-up of human figures, anticipates Pontormo for instance, by roughly 200 years!

3 The other and perhaps even more famous view of Arezzo is that in Arezzo itself, painted by Piero della Francesca in his extraordinary fresco cycle The Legend of the True Cross, in the church of St. Francis.

4 The term 'atmospheric perspective' refers to the creation of a sense of, often profound, depth in a painting through the use of various shades of, normally but not exclusively, blue; these very light, cool blues contrast markedly with the much stronger, purer and warmer colours used in the mid-ground and particularly the foreground of a particular picture. This effect can be realised in fresco, as for instance in the beautiful work of Alessio Baldovinetti: his Nativity in the front cloister of the church of the Santissima Annunziata in Florence. Giotto does not appear to use this device (fundamentally a change in tone) in the present fresco (colours much degraded admittedly) although in some others he does seem to be aware of it: in the Pope Honorius III listens to the preaching of Saint Francis, discussed later, the foreground colours are stronger than those used for the background.

5 The Birth and Rebirth of Pictorial Space by John White, published by Faber and Faber, 1972, page 27; first published 1957.